Bicomplex number

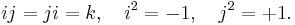

| × | 1 | i | j | k |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | i | j | k |

| i | i | −1 | k | −j |

| j | j | k | +1 | i |

| k | k | −j | i | −1 |

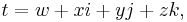

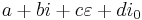

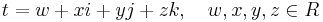

In mathematics, a tessarine is a hypercomplex number of the form

where

The tessarines are best known for their subalgebra of real tessarines  , also called split-complex numbers, which express the parametrization of the unit hyperbola. James Cockle introduced the tessarines in 1848 in a series of articles in Philosophical Magazine. Cockle used tessarines to isolate the hyperbolic cosine series and the hyperbolic sine series in the exponential series. He also showed how zero divisors arise in tessarines, inspiring him to use the term "impossibles."

, also called split-complex numbers, which express the parametrization of the unit hyperbola. James Cockle introduced the tessarines in 1848 in a series of articles in Philosophical Magazine. Cockle used tessarines to isolate the hyperbolic cosine series and the hyperbolic sine series in the exponential series. He also showed how zero divisors arise in tessarines, inspiring him to use the term "impossibles."

In 1892 Corrado Segre introduced bicomplex numbers in Mathematische Annalen, which form an algebra equivalent to the tessarines (see section below). As commutative hypercomplex numbers, the tessarine algebra has been advocated by Clyde M. Davenport (1991, 2008) (exchange j and −k in his multiplication table). Davenport has noted the isomorphism with the direct sum of the complex number plane with itself. Tessarines have also been applied in digital signal processing (see Pei (2004) and Alfsmann (2006,7). In 2009 mathematicians in Vermont proved a fundamental theorem of tessarine algebra: a polynomial of degree n with tessarine coefficients has n2 roots, counting multiplicity.

Contents |

Linear representation

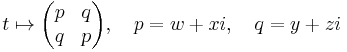

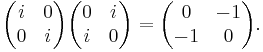

For tessarine  note that

note that  since ij = k . The mapping

since ij = k . The mapping

is a linear representation of the algebra of tessarines as a subalgebra of 2 x 2 complex matrices. For instance, ik = i(ij) = (ii)j = −j in the linear representation is

Note that unlike most matrix algebras, this is a commutative algebra.

Isomorphisms to other number systems

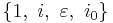

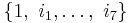

In general the tessarines form an algebra of dimension two over the complex numbers with basis {1, j }

Bicomplex number

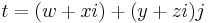

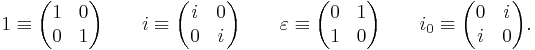

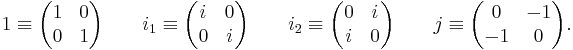

Corrado Segre read W. R. Hamilton's Lectures on Quaternions (1853) and the works of William Kingdon Clifford. Segre used some of Hamilton's notation to develop his system of bicomplex numbers: Let h and i be square roots of −1 that commute with each other. Then, presuming associativity of multiplication, the product hi must have +1 for its square. The algebra constructed on the basis {1, h, i, hi} is then nearly the same as James Cockle's tessarines. Segre noted that elements

are idempotents.

are idempotents.

When bicomplex numbers are considered to have basis {1, h, i, −hi} then there is no difference between them and tessarines. Looking at the linear representation of these isomorphic algebras shows agreement in the fourth dimension when the negative sign is used; just consider the sample product given above under linear representation.

The University of Kansas has contributed to the development of bicomplex analysis. In 1953, a Ph.D. student James D. Riley had his thesis "Contributions to the theory of functions of a bicomplex variable" published in the Tohoku Mathematical Journal (2nd Ser., 5:132–165). Then, in 1991, emeritus professor G. Baley Price published his book on bicomplex numbers, multicomplex numbers, and their function theory. Professor Price also gives some history of the subject in the preface to his book. Another book developing bicomplex numbers and their applications is by Catoni, Bocaletti, Cannata, Nichelatti & Zampetti (2008).

Direct sum C + C

The direct sum of the complex field with itself is denoted  . The product of two elements

. The product of two elements  and

and  is

is  in this direct sum algebra.

in this direct sum algebra.

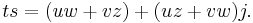

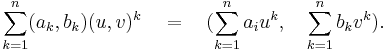

Proposition: The algebra of tessarines is isomorphic to

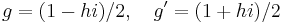

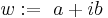

proof: Every tessarine has an expression  where u and v are complex numbers. Now if

where u and v are complex numbers. Now if  is another tessarine, their product is

is another tessarine, their product is

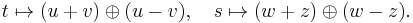

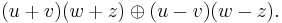

The isomorphism mapping from tessarines to  is given by

is given by

In  , the product of these images, according to the algebra-product of

, the product of these images, according to the algebra-product of  indicated above, is

indicated above, is

This element is also the image of ts under the mapping into  Thus the products agree, the mapping is a homomorphism; and since it is bijective, it is an isomorphism.

Thus the products agree, the mapping is a homomorphism; and since it is bijective, it is an isomorphism.

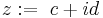

Conic quaternion / octonion / sedenion, bicomplex number

When w and z are both complex numbers

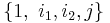

(a, b, c, d real) then t algebra is isomorphic to conic quaternions  , to bases

, to bases  , in the following identification:

, in the following identification:

They are also isomorphic to "bicomplex numbers" (from multicomplex numbers) to bases  if one identifies:

if one identifies:

Note that j in bicomplex numbers is identified with the opposite sign as j from above.

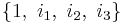

When w and z are both quaternions (to bases  ), then t algebra is isomorphic to conic octonions; allowing octonions for w and z (to bases

), then t algebra is isomorphic to conic octonions; allowing octonions for w and z (to bases  ) the resulting algebra is identical to conic sedenions.

) the resulting algebra is identical to conic sedenions.

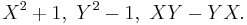

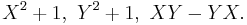

Quotient rings of polynomials

A modern approach to tessarines uses the polynomial ring R[X,Y] in two indeterminates X and Y. Consider these three second degree polynomials  Let A be the ideal generated by them. Then the quotient ring R[X,Y]/A is isomorphic to the ring of tessarines. In this quotient ring approach, individual tessarines correspond to cosets with respect to the ideal A. Note that

Let A be the ideal generated by them. Then the quotient ring R[X,Y]/A is isomorphic to the ring of tessarines. In this quotient ring approach, individual tessarines correspond to cosets with respect to the ideal A. Note that  can be proven using computations with cosets.

can be proven using computations with cosets.

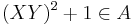

Now consider the alternative ideal B generated by  In this case one can prove

In this case one can prove  The ring isomorphism

The ring isomorphism ![R[X,Y]/A \ \cong \ R[X,Y]/B](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d971b850ec55b517b44be5239dba90fa.png) involves a change of basis exchanging

involves a change of basis exchanging  The approach to tessarines by James Cockle resembles the use of ideal A, while Corrado Segre's bicomplex numbers correspond to the use of ideal B.

The approach to tessarines by James Cockle resembles the use of ideal A, while Corrado Segre's bicomplex numbers correspond to the use of ideal B.

Alternatively, suppose the field C of ordinary complex numbers is presumed given, and C[X] is the ring of polynomials in X with complex coefficients. Then the quotient ![C[X]/<X ^2 - 1>](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7337714cce92765be80f44edc5c99128.png) is another presentation of bicomplex numbers.

is another presentation of bicomplex numbers.

Algebraic properties

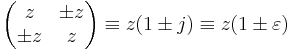

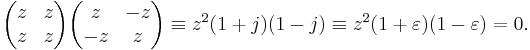

Tessarines with w and z complex numbers form a commutative and associative quaternionic ring (whereas quaternions are not commutative). They allow for powers, roots, and logarithms of  , which is a non-real root of 1 (see conic quaternions for examples and references). They do not form a field because the idempotents

, which is a non-real root of 1 (see conic quaternions for examples and references). They do not form a field because the idempotents

have determinant / modulus 0 and therefore cannot be inverted multiplicatively. In addition, the arithmetic contains zero divisors

In contrast, the quaternions form a skew field without zero-divisors, and can also be represented in 2×2 matrix form.

Polynomial roots

Write  and represent elements of it by ordered pairs (u,v) of complex numbers. Since the algebra of tessarines T is isomorphic to

and represent elements of it by ordered pairs (u,v) of complex numbers. Since the algebra of tessarines T is isomorphic to  , the rings of polynomials T[X] and

, the rings of polynomials T[X] and  [X] are also isomorphic, however polynomials in the latter algebra split:

[X] are also isomorphic, however polynomials in the latter algebra split:

In consequence, when a polynomial equation  in this algebra is set, it reduces to two polynomial equations on C. If the degree is n, then there are n roots for each equation:

in this algebra is set, it reduces to two polynomial equations on C. If the degree is n, then there are n roots for each equation:  Any ordered pair

Any ordered pair  from this set of roots will satisfy the original equation in 2C[X], so it has n2 roots. Due to the isomorphism with T[X], there is a correspondence of polynomials and a correspondence of their roots. Hence the tessarine polynomials of degree n also have n2 roots, counting multiplicity of roots.

from this set of roots will satisfy the original equation in 2C[X], so it has n2 roots. Due to the isomorphism with T[X], there is a correspondence of polynomials and a correspondence of their roots. Hence the tessarine polynomials of degree n also have n2 roots, counting multiplicity of roots.

References

- Daniel Alfsmann (2006) On families of 2^N dimensional hypercomplex algebras suitable for digital signal processing, 14th European Signal Processing Conference, Florence, Italy.

- Daniel Alfsmann & Heinz G Göckler (2007) On Hyperbolic Complex LTI Digital Systems

- F. Catoni, D. Boccaletti, R. Cannata, V. Catoni, E. Nichelatti, P. Zampetti. (2008) The Mathematics of Minkowski Space-Time with an Introduction to Commutative Hypercomplex Numbers, Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel ISBN 978-3-7643-8613-9.

- James Cockle in London-Dublin-Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine, series 3

- 1848 On Certain Functions Resembling Quaternions and on a New Imaginary in Algebra, 33:435–9.

- 1849 On a New Imaginary in Algebra 34:37–47.

- 1849 On the Symbols of Algebra and on the Theory of Tessarines 34:406–10.

- 1850 On Impossible Equations, on Impossible Quantities and on Tessarines 37:281–3.

- Clyde Davenport (1991) A Hypercomplex Calculus with Applications to Special Relativity ISBN 0-9623837-0-8 .

- Clyde Davenport (2008) Commutative Hypercomplex Mathematics.

- Soo-Chang Pei, Ja-Han Chang & Jian-Jiun Ding (2004) "Commutative reduced biquaternions and their Fourier transform for signal and image processing", IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 52:2012–31.

- G. Baley Price (1991) An introduction to multicomplex spaces and functions, Marcel Dekker ISBN 082478345X .

- Corrado Segre (1892) "The real representation of complex elements and hyperalgebraic entities" (Italian), Mathematische Annalen 40:413–67 (see especially pages 456–60).

|

|||||||||||

)

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

)